Researchers are working on a way for soldiers to generate heat in cold environments instead of piling on multiple bulky layers to their uniforms.

By applying a silver nanowire coating to the uniforms, troops could theoretically dial up the heat to keep themselves comfortable, according to researchers at U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center in Massachusetts.

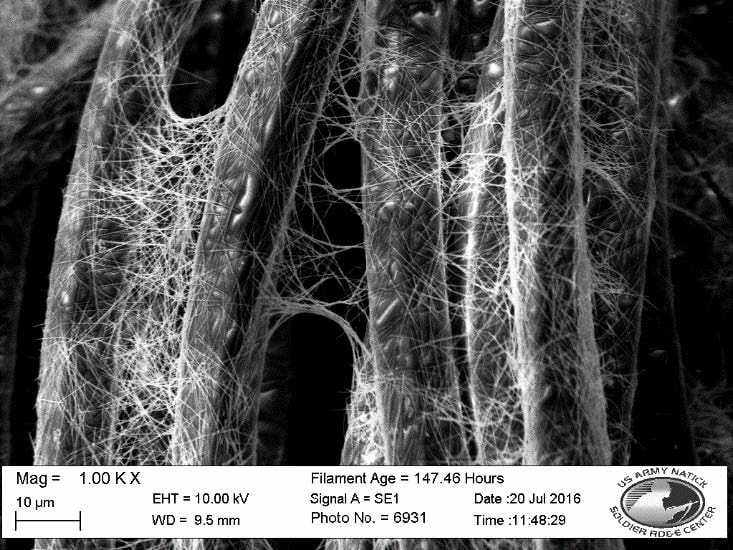

The silver nanowires form an electrically conductive network that when hooked up to a low-power battery can heat up polyester and polypropylene, research bioengineer Paola D’Angelo told Army Times.

The goal is to coat gloves with the material and eventually apply it to the entire uniform.

“If we reduce the number of layers [troops have to wear], they still keep that dexterity that allows them to operate weapons and machinery,” D’Angelo said.

Right now, D’Angelo and her team have been coating a swatch of material that’s a couple of inches square. They dip the material in the silver nanowire coating for about 45 minutes to an hour, then it’s exposed to a temperature of 150 degrees Celsius for about 30 minutes to fuse the nanowires together. This improves the electrical conductance, she said.

The swatch is hooked up to a power supply and passing between .5 to 3 volts — similar to that of a watch battery.

D’Angelo said they’re going to collaborate with a professor from the University of California-San Diego who developed a flexible battery that would work better with the silver nanowire coating.

This battery is about as thick as a piece of tape and weighs almost nothing, which is important, she said. It will go either in the cuff of the glove or on top of it.

“You can flex it and bend it and stretch it and it still performs the same,” D’Angelo said. “We obviously want to try to avoid using battery packs because we don’t want to add any weight to the soldier.”

The project is still in the basic research stage, and D’Angelo said it will be several years before troops will receive silver nanowire-coated items.

“If everything goes as expected, we’ll probably move on to socks to prevent frostbite,” she said. “If that goes well, we’d go to the base layer.”

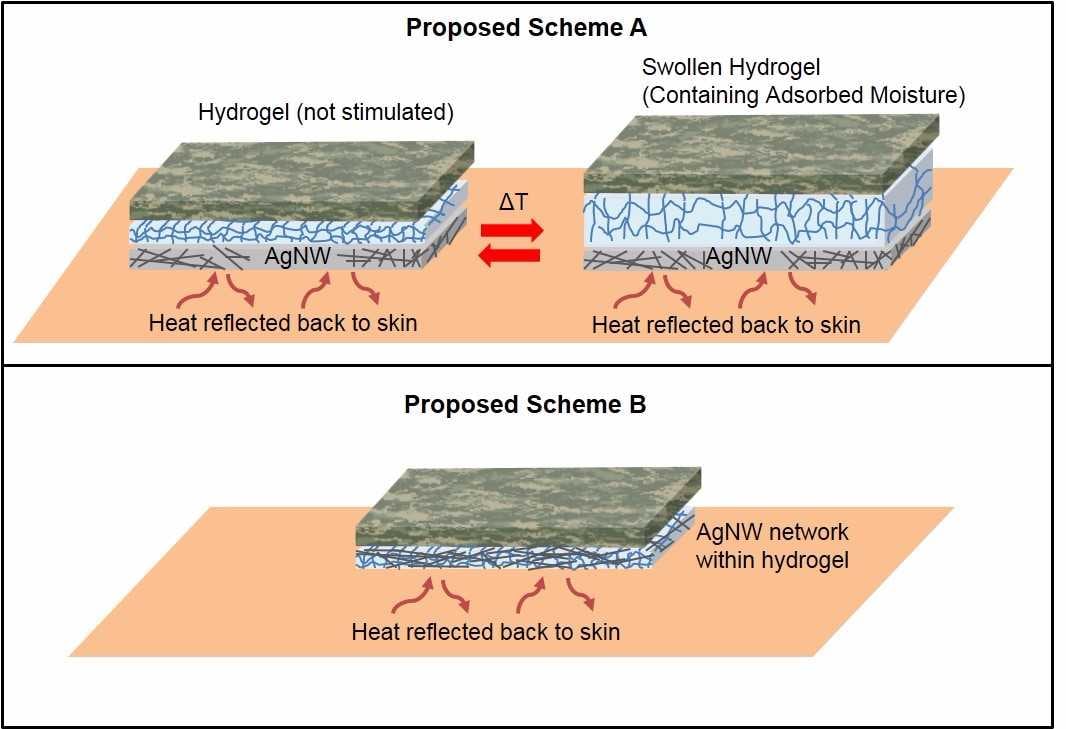

Elizabeth Hirst, a research chemist at Natick, is working on a moisture-absorbing hydrogel to complement D’Angelo’s coating work.

“The idea with the hydrogel is adding a coating or particle coating that helps increase the wicking ability of the fabric at very cold temperatures,” Hirst said.

Although polyurethane is already moisture wicking, Hirst said the problem is if any moisture turns to ice before it has a chance to evaporate.

“Then you get ice spots around the wrists, neck, anywhere you’re really sweating heavily,” she said.

The absorbent hydrogel coating would prevent that from happening.

There has been a lot of research on hydrogels at warmer temperatures, Hirst said, but not much is known about what happens to them at cold temperatures.

Hirst’s team has confirmed that hydrogels will still absorb moisture even if the gel freezes, and the next step is to test it on swatches of material, like D’Angelo’s team did with the silver nanowire.

One of the next steps is to research how well the coating holds up to being washed, and if there are any potential risks to the soldier.

They want to make sure they can protect the battery from moisture, as well as keeping the system from heating up too much.

“One nice thing is even if the battery fails,” Hirst said, “the nanowires themselves are very good infrared reflectors.”

The coating will bounce back your own body heat, so the nanowires can provide some heat even without a battery.

D’Angelo said the team wants soldiers to be able to dial the heat up or down depending on the environment and their needs.

“Maybe a 10-15 degree difference would benefit the soldier and would make it comfortable for them in such a way that they don’t have to wear as many layers,” she said.

The goal is to increase soldier performance and readiness, D’Angelo said.

“It will take a little bit more research to get up there,” she said. “But we’re hopeful this will improve the cold-weather uniform.”

Charlsy is a Reporter and Engagement Manager for Military Times. Email her at cpanzino@militarytimes.com.