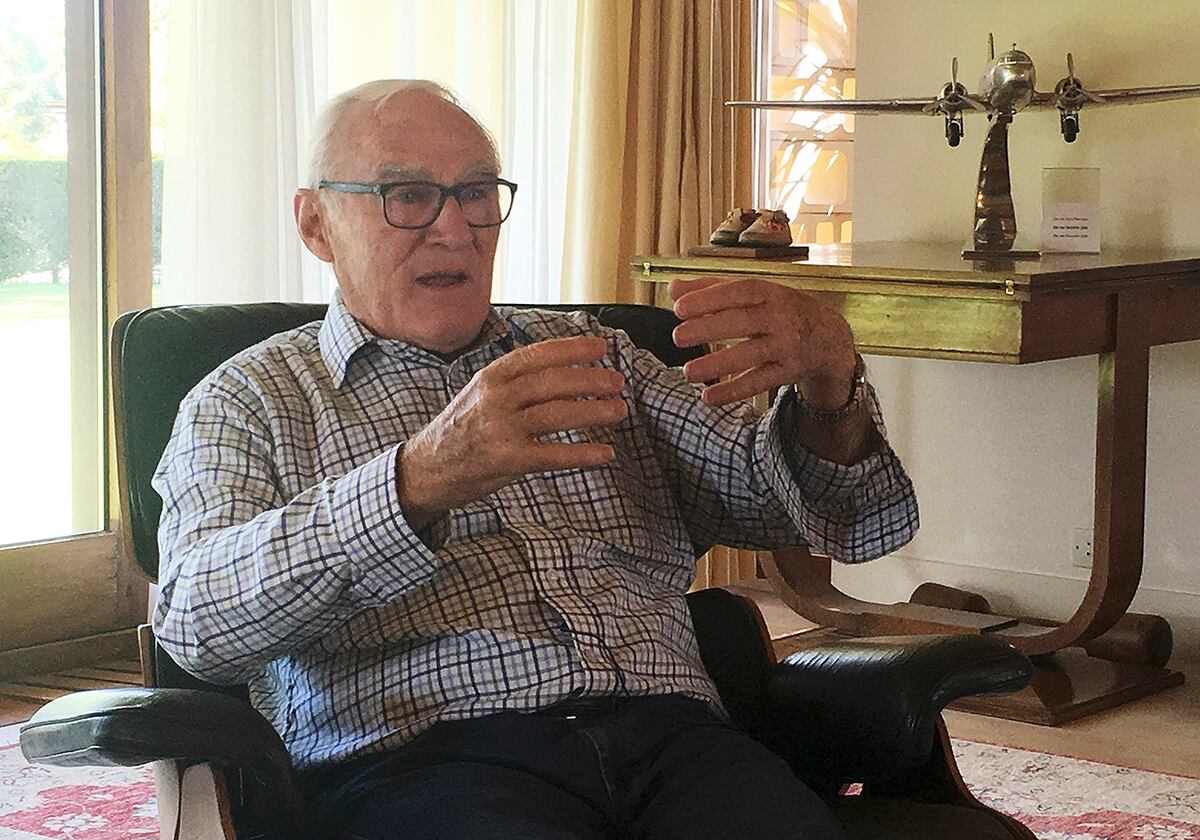

SAINTE-MERE-EGLISE, France — At 10 years old, Henri-Jean Renaud watched U.S. paratroopers landing through the window of his Normandy home in the early hours of D-Day. Like other French who lived through the war, he’s trying to pass on to younger generations the gratitude he feels.

With fewer veterans and witnesses able to share personal memories, the French who owe their freedom to D-Day’s fighters are more determined than ever to keep alive the memory of the battle and its significance.

President Donald Trump and other world leaders will gather next week in Normandy to mark the 75th anniversary of the invasion, which still looms large throughout this region. Normandy beaches, cemeteries and World War II memorials embody what French President Macron called “our entire nation’s infinite gratitude.”

RELATED

Renaud, now 85, recalls the strange atmosphere in Sainte-Mere-Eglise, the first village liberated by the Allies, on the morning of June 6, 1944. He could hear the fighting at a short distance but in the village, everything was calm.

“The civilians came down on the pavement and tried to fraternize with the Americans by making victory signs, waving hello, etc. But there hasn’t been any fraternization from the Americans because — you have to put yourself in their shoes — they were very nervous, very anxious. They had their finger on the trigger,” Renaud said.

Fraternization came later.

All his life, Renaud has taken care of veterans, hosting them and helping them visit the former battlefields, “because nothing touched me more than seeing those guys who were coming back, searching for the place where they were dropped, the place where they lost a friend.”

About 15,000 paratroopers landed in and around Sainte-Mere-Eglise not long after midnight on June 6, 1944, and seized it from the Germans by 4:30 a.m. An American flag was raised in front of the town hall.

“It was making a lot of noise and the planes were flying low,” recalled 97-year-old Albert Guégan, a French civilian survivor living in Carentan, a few kilometers away. “We were in a ditch near our house with the neighbors. We thought we would be hit by bombs. But no, it was not a bombing. It was the paratroopers!”

RELATED

More than 150,000 troops crossed the English Channel on D-Day, and more than 2 million Allied troops were in France by the end of August.

Among them was Frank Mouqué, who landed on Sword Beach as a 19-year-old corporal with the British Royal Engineers. Now 94, he has returned to Normandy more than 30 times at the invitation of a French family.

“It’s marvelous, the way we’re treated! They’re so pleased to welcome a veteran in that sense. You sit outside in the coffee shop, having early morning cup of coffee and people come up and shake your hand and say: ‘Merci, merci beaucoup. You are our savior!’”

British veteran Jack Woods has also returned to Normandy many times. As soon as the bus stops, he walks down to the cafe near the cathedral in Bayeux, where the owner tells everyone to clear out to make room for his friends from Britain.

“They go mad,” the 95-year-old said of his reception, adding that they always have “a whale of a time.”

Even amid the warmth, the trip is always a serious matter for him. He feels he has no choice.

RELATED

Woods fought with the 9th Royal Tank Regiment and got to France at the end of June 1944, a few weeks after D-Day. But fighting was still intense, and many of the soldiers had never seen combat.

“I promised them I would not forget them,” he said of the pact he made with his fellow soldiers when he was just 20. “I can’t not go. We go over there and be with them — all these guys.”

Near Omaha Beach, the beauty of the American cemetery of Colleville-sur-Mer strikes any visitor entering the site, with its immaculate lawns, majestic pines, commanding view of the Atlantic and row upon row of crosses.

The cemetery contains 9,380 graves, most of them for servicemen who lost their lives in the D-Day landings and ensuing operations. Another 1,557 names are inscribed on the Walls of the Missing.

Alain Dupain, 61, is a gardener who has worked at the cemetery for 35 years, maintaining the grounds with a team of 20 people.

"We work for the families. When they come, we want the site to be perfect for them and their tombs ... And I think if one of your loved ones dies and you arrive at a beautiful, well-maintained place like that, it will not erase the pain but might bring a little bit of relief."

RELATED

The site receives approximately 1 million visitors each year.

Superintendent Scott Desjardins of the American Battle Monuments Commission said the top priority “is to keep this site at the highest standards possible because it is the promise we made to the families who decided to keep their loved ones with us. It overrides every other priority.”

The memorial of Colleville-sur-Mer also aims to preserve soldiers’ stories, he added. “So we’ll continue to say their names. And continue to tell people what it is that they did.”

Normandy has more than 20 military cemeteries holding mostly Americans, Germans, French, British, Canadians and Polish.

Karen Lancelle, 42, who grew up in Colleville-sur-Mer, has been a guide at the cemetery for 12 years. She said the memory of the battle is still alive among children in the region thanks to frequent school visits and family stories told by older generations.

The cemetery is a place “where meetings can happen between the veterans and the youngest ones.” Nearly every day brings some kind of touching moment with American families, she said.

While visiting the cemetery, Vietnam veteran Tom Woolbright, 75, from Fort Worth, Texas, insisted on thanking the people of France “for maintaining and for honoring the men who died on that day ... in such a beautiful fashion like this cemetery.”

“This bonds us, and a war like that should never happen again,” Woolbright said.

Corbet reported from Paris. Associated Press writers Raf Casert in Colleville-sur-Mer and Danica Kirka in London contributed to this report.