NEAR BAKHMUT, UKRAINE — Russian forces spearheaded by the infamous Wagner private military group are steadily wearing down the last holdouts in the city of Bakhmut, with the nearly encircled Ukrainians taking heavy casualties and running out of firepower, after a monthslong fight.

British and American legionnaires with Ukraine’s International Legion who just left Bakhmut tell Military Times that Ukrainian forces lack the basics — mechanized vehicles and artillery ammunition — to keep up the fight, with the Russians slowly squeezing the city in a north-south pincer movement. But Ukraine’s high command refuses to abandon the city, counting on the grinding warfare to bleed Russian manpower and materiel, kneecapping any wider Russian spring offensive.

Indeed, the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington-based think tank, reports that Russian forces haven’t even managed to cross the river that partitions Bakhmut, and nor do Russians appear to have the combat power to expand further westward beyond the besieged city.

“Bakhmut must stand” said Sam, a 37-year-old former U.S. Marine gunner with tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, echoing determined Ukrainian officials. Speaking to Military Times near Konstantinovka, outside of Bakhmut, the veteran acknowledged heavy losses defending the city, including his unit’s translator and senior officer, but said it has “symbolic significance.”

To keep holding Bakhmut, the Ukrainian troops need to be resupplied, fast. Troops complain that they have so little ammunition that artillery units are forced to pick and choose which fellow troops under fire to help. The soldiers said Ukraine’s military leadership may be hoarding shells for the upcoming larger offensive, griping that shows plummeting morale.

That frustration is what drove troops to speak out, most only giving first names or asking to remain anonymous, for fear their commanders would censure them for their criticism.

Ukrainian defense officials did not respond to requests for comment, as their troops fight on, staving off a rout of Bakhmut, for now.

Six miles from the front

Chasiv Yar, a small town about six miles west of the besieged city, hosts an unknown number of Ukrainian artillery pieces hidden throughout the town, their blasts of fire reverberating through the nearly empty streets, in support of Ukrainian forces miles away.

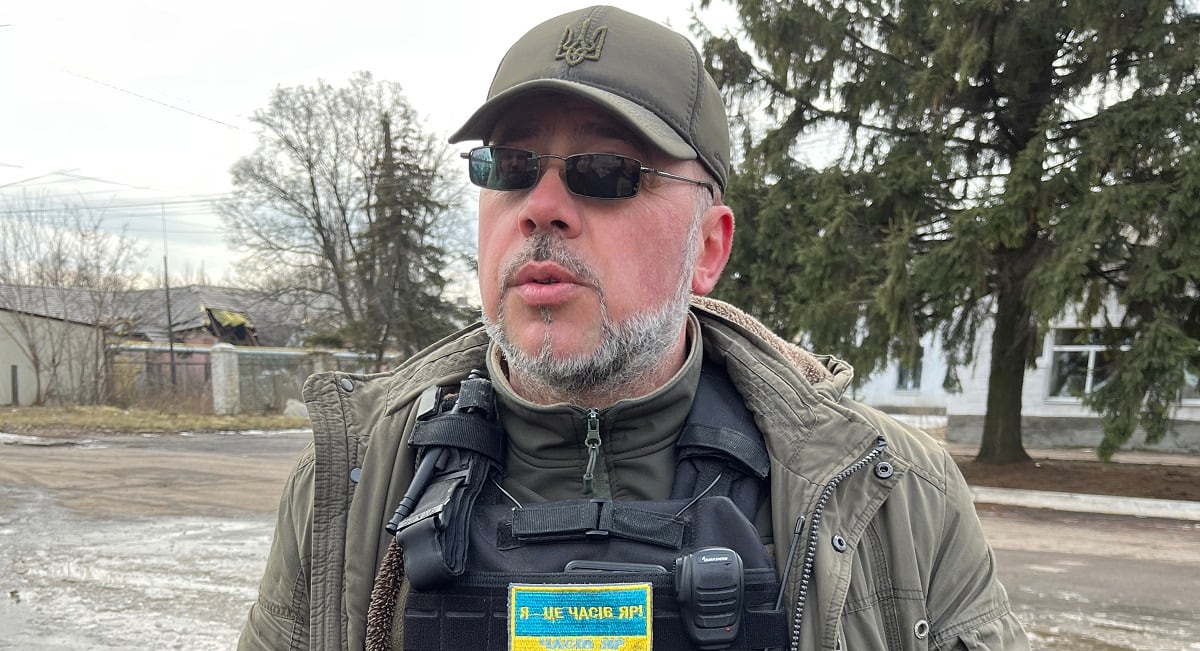

Sergey Chaus, the head of Chasiv Yar’s civilian and military administration, bluntly described the situation in the town as “stably fucked.” Speaking frankly about the military situation, he reflected on the town’s importance to the operation around Bakhmut.

The town is essential “because it’s practically the only road into Bakhmut” and would be an important lifeline to safety should Ukrainian forces pull back westward.

With Russians focusing on Bakhmut, Chasiv Yar is spared from the volume of shelling that Bakhmut withstands, though the city is far from safe. Russian incoming happens “all the time,” Chaus said, adding that a volley from a Russian Grad multiple rocket launcher pummeled apartments throughout the town earlier last week.

In Konstantinovka to the southwest, a Ukrainian combat medic named Alexsander said he’s treating trauma caused by bullets and shrapnel, and a high number of concussions, the kind of wounds caused by nearby explosions that are invisible but nonetheless debilitating.

The fighting around Bakhmut is “like 2014,” Alexsander said, a reference to this conflict’s early years in the east after the Russians seized Crimea and kept marching toward the Donbas. Front lines froze into a World War I-style battle of attrition fought from static, dug-in positions.

Besides basic emergency first-aid like applying tourniquets, blood transfusions and stitches, there is little more he can do in the field to save Ukraine’s wounded. On his hand, a tattoo of a syringe reads “HOPE” in bold lettering. He wishes he had more advanced medical treatment options to give the injured more than hope.

Russian manpower reserves are, if not of a high caliber, deep. Armed with little more than assault rifles and ammunition, waves of recently mobilized Russians bellycrawl from their lines through crater-pocked no-man’s land toward Ukrainian forces arrayed in and around the beleaguered city.

Alexsander added that Russian and Ukrainian forces sometimes fire at each other at point-blank range, directly “shooting from trenches,” which is a very different battle than during last summer, when troops often fought each other from a greater distance. Firing that close produces even more brutal injuries.

Green troops on all sides

That close fight also means both sides are losing senior officers and troops with advanced training and expertise. Though Russia’s Wagner group was once a powerful presence on the battlefield, the recent injection of new conscripts and convicts from prisons across Russia has diluted the fighting force’s potency. Russians sent to the front are often poorly trained and often must buy their own equipment.

And the Ukrainians sent to replace their fallen and injured often have just two weeks’ basic training, a lack of preparation that partly helps to explain Ukraine’s heavy losses in Donbas.

NATO-led training initiatives in Germany, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere across Europe, aim to raise multiple brigades of trained Ukrainian soldiers, but could take until mid to late summer to yield results. The British Defence Ministry’s program will take roughly four months to turn out 10,000 soldiers.

But even with that pipeline ramping up, Ukrainian officials worry that the longer the war goes on, they may be forced to throw increasingly untrained troops into the breach, arrayed against a country with a significantly larger population than Ukraine. Moscow’s ability to rapidly conscript and ship hundreds of thousands of men dwarfs Ukraine’s manpower reserves.

High-tech equipment to help make up for that personnel disparity is pouring into Ukraine at a clip not seen since the start of the full-scale invasion. Speaking to reporters March 15, Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III stated that NATO must supply Ukraine with the “training, spare parts and maintenance support” that Ukrainian soldiers need “to use these new systems as soon as possible.”

That will help, but Marine Corps veteran Sam says the incoming Western tanks and other advanced equipment, “aren’t a silver bullet.” He and the other expats said Ukrainian forces also need just about everything, from specialized equipment like mine clearing hardware to more armored trucks, instead of the soft-skinned jeeps and passenger vans they’ve scrounged into service after losing so many armored vehicles to Russian assault.

Case in point: Eugene, a tall Virginian, spends his days working to keep a Nissan SUV running in a war zone. On Konstantinovka’s outskirts, he pulls on a Marlboro and scratches at some dried blood caked on his face as he checks the fluid levels, lamenting that “Something is rubbing one of the tires.”

Sam tried to end on a high note, insisting that Ukraine is slowly but surely transforming into a professionalized force equipped with NATO-standard weaponry, given sufficient time to integrate those weapons, expand training and leverage spare parts for NATO systems.

But to hold the Russians off in the close, grinding fight of Bakhmut, they need the basics: ammunition, artillery shells and armored vehicles to fight on, or get out.

In Donbas, Sam explained, “every trench is its own battle.”

Caleb Larson is a multimedia journalist based in Berlin. He covers the intersection of conflict, politics, and technology, focusing on U.S. foreign policy and European security. In addition to time spent reporting from Russia, Germany, and the U.S., he also covers the war in Ukraine, reporting from multiple front-line areas throughout the country.