SEOUL, South Korea — Bill Clinton offered oil and reactors. George W. Bush mixed threats and aid. Barack Obama stopped trying after a rocket launch.

A decades-long cycle of crises, stalemates and broken promises gave North Korea the room to build up a legitimate arsenal that now includes purported thermonuclear warheads and developmental ICBMs. The North’s latest announcement stopped well short of suggesting it has any intention of giving that up.

RELATED

South Korean President Moon Jae-in meets with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un on Friday to kick off a new round of high-stakes nuclear diplomacy with Pyongyang. The inter-Korean summit could set up more substantial discussions between Kim and President Donald Trump, who said he plans to meet the dictator he previously called “Little Rocket Man” in May or June.

A look at previous negotiations with North Korea and how the currently planned summits took shape:

1994

The Clinton administration in October 1994 reached a major nuclear agreement with Pyongyang, ending months of war fears triggered by North Korea’s threat to withdraw from the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and convert its stockpile of nuclear fuel into bombs.

Under the “Agreed Framework,” North Korea halted construction of two reactors the United States believed were for nuclear weapons production in return for two alternative nuclear power reactors that could be used to provide electricity but not bomb fuel, and 500,000 metric tons of fuel oil annually for the North.

The deal was tested quickly. North Korea complained about delayed oil shipments and construction of the reactors, which were never delivered. The United States criticized the North’s pursuit of ballistic missile capability, demonstrated in the launch of a two-stage rocket over Japan in 1998.

The Agreed Framework further lost political support in Washington with the inauguration of Bush, who in his first State of the Union address in January 2002 grouped North Korea with Iran and Iraq as parts of an “axis of evil.”

The deal collapsed for good months later after U.S. officials confronted North Korea over a clandestine nuclear program using enriched uranium. Washington stopped the oil shipments and Pyongyang restarted its nuclear weapons program.

RELATED

2005

Responding to Washington’s toughened stance, North Korea announced in 2003 that it obtained a nuclear device and would withdraw from the Nonproliferation Treaty.

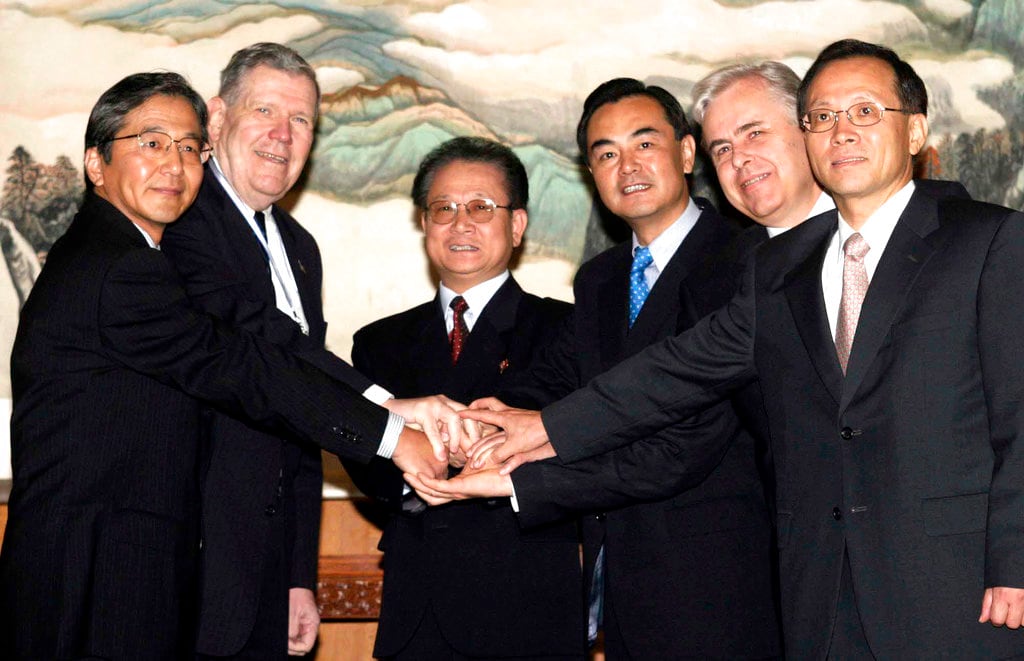

This brought the United States back to the negotiating table with the North, and six-party talks also involving South Korea, China, Japan and Russia began in Beijing in August 2003.

After months of fiery negotiations, North Korea accepted a deal in September 2005 to end its nuclear weapons program in exchange for security, economic and energy benefits.

But the agreement was shaky from the start as it came just days after the U.S. Treasury Department ordered American banks to sever relations with a Macau bank accused of helping North Korea launder money from drug trafficking and other illicit activities, which hampered Pyongyang’s international financial transactions.

Disagreements between Washington and Pyongyang over the financial punishment of Banco Delta Asia temporarily derailed the six-nation talks. In October 2006, the North went on to conduct its first nuclear test.

RELATED

2007

North Korea agreed to resume the six-nation disarmament talks a few weeks after the nuclear test. In February 2007, the United States and the four other countries reached an agreement to provide North Korea with an aid package worth about $400 million in return for the North disabling its nuclear facilities and allowing international inspectors back into the country.

North Korea demolished the cooling tower at its Nyongbyon reactor site in June 2008. But in September, the North declared that it would resume reprocessing plutonium, complaining that Washington wasn’t fulfilling its promise to remove the country from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism.

The Bush administration removed North Korea from the list in October 2008 after the country agreed to continue disabling its nuclear plant. However, a final attempt by Bush to complete an agreement to fully dismantle North Korea’s nuclear weapons program collapsed in December when the North refused to accept U.S.-proposed verification methods.

The six-nation talks have stalled since then. The North conducted its second nuclear test in May 2009, months after Obama took office.

2012

Months after taking power following the death of his father, current North Korean leader Kim reached a deal with the Obama administration in February 2012 to suspend nuclear weapons and missile tests and uranium enrichment and to also allow international inspectors to monitor its nuclear activities in exchange for U.S. food aid.

The United States killed the deal in April 2012 when the North launched a long-range rocket that it claimed was built for delivering satellites. The failed launch was seen by the outside world as a prohibited test of ballistic missile technology.

The North criticized the United States of “overreacting” and launched another long-range rocket in December 2012 that it said successfully delivered a satellite into space.

In 2013, Kim announced that his government would pursue a national “byungjin” policy aimed at simultaneously seeking nuclear development and economic growth. This was seen as a clean break from the North’s previous stance that mainly used the nuclear program as a bargaining chip to extract concessions from foreign governments, rather than for immediate military purposes.

2018

North Korea’s abrupt diplomatic outreach in recent months comes after a flurry of 2017 weapons tests, including the underground detonation of an alleged thermonuclear warhead and three launches of developmental ICBMs designed to strike the U.S. mainland.

Inter-Korean dialogue resumed after Kim in his New Year’s speech proposed talks with the South to reduce animosities and for the North to participate in February’s Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. North Korea sent hundreds of people to the games, including Kim’s sister, who expressed her brother’s desire to meet with South Korean President Moon for a summit. South Korean officials later brokered a potential summit between Kim and Trump.

While South Korean and U.S. officials have said Kim is likely trying to save his broken economy from heavy sanctions, some analysts see him as entering the negotiations from a position of strength after having declared his nuclear force as complete in November.

Seoul has said Kim expressed genuine interest in dealing away his nuclear weapons. But North Korea for decades has been pushing a concept of “denuclearization” that bears no resemblance to the American definition, vowing to pursue nuclear development unless Washington removes its troops from the Korean Peninsula and the nuclear umbrella defending South Korea and Japan.

Some experts say Kim’s nuclear program is now too advanced to realistically expect a roll back to near zero.

“Kim will not offer CVID at the door,” said Koh Yu-hwan, a North Korea expert at Seoul’s Dongguk University, who is advising Moon on his summit with Kim. He was referring to an abbreviation for the “complete, verifiable and irreversible dismantlement” of the North’s nuclear weapons program.

“Everything depends on whether Trump can accept a deal that puts out the ‘early fire’ — taking away the North’s ICBMs and freezing and closing its known nuclear and missile production facilities — and leave the rest for future negotiations,” Koh said.