When former Army specialist Matt Hesse founded FitOps in 2016, he saw the organization as a way to give veterans a purpose outside the military.

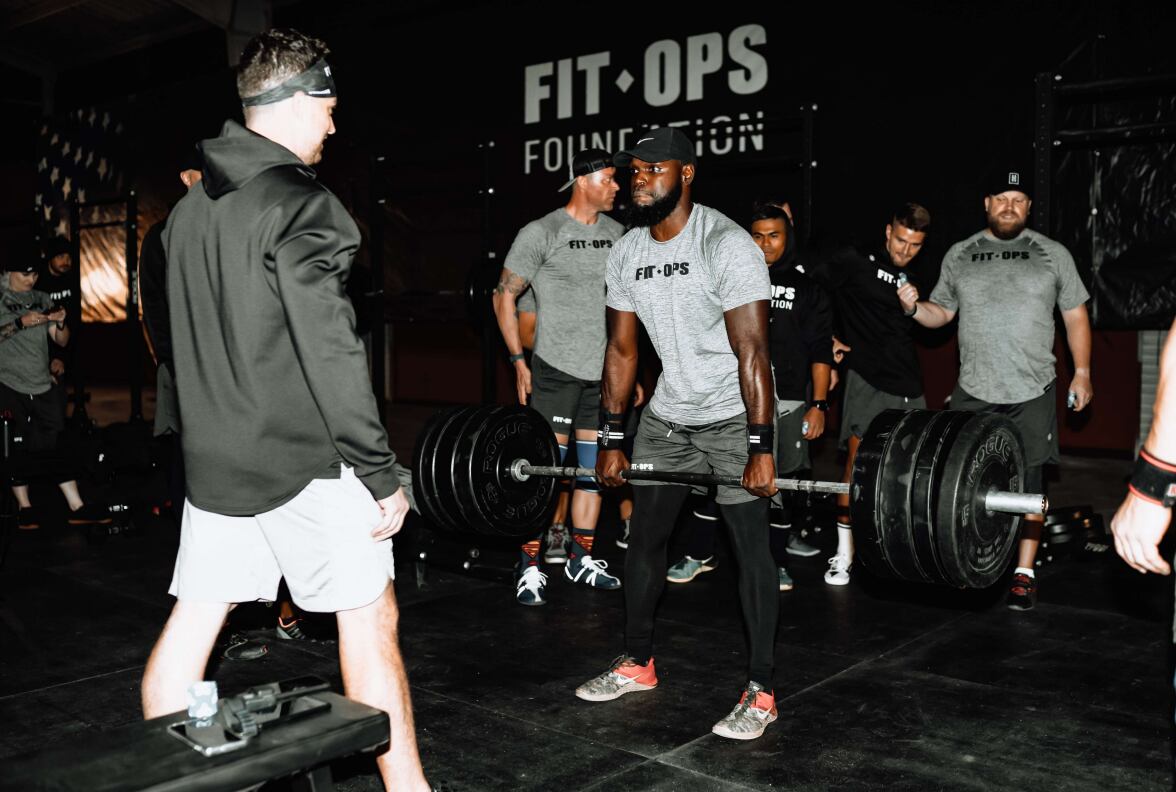

Under its initial design, students would undergo three weeks of intense training and education to become certified veteran fitness operatives equipped with the skills to give back to their communities and earn a living as personal trainers.

From early morning PT through evening training sessions and workshops, Hesse had put together a functional certification program. As the CEO and founder of supplement and nutrition brand Performix, FitOps’ founder would also leverage his knowledge of the industry to connect graduates with a vast network of employers across the country.

But on the first night of the program’s first camp, everything changed. Hesse sat down in a room with nearly 60 veterans struggling to navigate the complex transition to civilian life and saw the need they had for support and community — things FitOps trainers could provide to one another.

“It quickly evolved from a fitness mission to a mental health and community-driven mission with the intention of still certifying veterans as personal trainers but also giving them a network and support structure of fellow veterans across the country,” said Harrison Johnson, a former Army staff sergeant and director of operations for FitOps.

The program now consists of a nine-week pre-study course leading up to a three-week training camp where students are exposed to world-class fitness and mental health experts, celebrity bodybuilders, and business professionals who teach them to start and run a personal training business of their own.

It’s big business. Personal trainers earned nearly $4 billion last year, according to an industry market research study.

But what Johnson is most proud of is the continued support FitOps is able to provide to its graduates through the organization’s aftercare initiatives.

Once they’ve gone through the initial training camp, veterans become part of the FitOps community, where they are in constant contact with a support network and granted access to additional certifications, workshops and continued group interactions.

FitOps even goes so far as to offer couples and addiction counselling to graduates in need of such services.

But when the coronavirus pandemic hit in early 2020, FitOps was forced to temporarily close the doors on its training camp.

Though it could no longer offer opportunities for new students to get certified, FitOps wasn’t going to let the pandemic get in the way of supporting its graduates – graduates whose businesses were struggling under COVID-19 restrictions.

That’s where Vincent Miceli and the coaching application Verb stepped in.

Building accountability

A New Yorker through and through, Miceli had spent the early years of his career starting businesses and investing on Wall Street. Along the way, the entrepreneur picked up some bad habits.

Describing himself as 5-foot-6-and-a-half on a good day, Miceli says he was bordering on 250 pounds when he finally decided to turn his life around.

“I spent a lot of time understanding how food interacts with my body, paying attention to some of the habits I might’ve been neglecting while building my career in my early twenties, and ultimately lost 100 pounds in a year,” Miceli said.

For the better part of a decade now, he’s been heavily involved in the health and fitness industry, building and working with gyms in southern New York.

Inspired by constant questions from his gym members asking how he’s achieved his successes and how they can reach their own goals, Miceli decided to write a book exploring success and accountability.

He asked five people to send him daily video updates for 60 days on their efforts to achieve a personal goal, and by the end, each participant was intended to become a chapter in his book. Instead, the videos became the basis for Miceli’s newest business initiative.

“Those five people, besides the fact that they all changed their lives drastically in about 60 days, invited roughly another 90 people to do the same thing,” said Miceli.

Soon, the New York businessman was wading through hours of videos every morning. One of his participants suggested starting a business based on what he had learned about personal accountability.

After a little convincing and an investment from a participant, Miceli partnered with artificial intelligence expert Artur Kiulian to create an application that would help people meet their goals.

That app, Verb, was up and running in no time.

Using text messages, Verb fuses the power of AI and certified human coaches to qualitatively measure clients’ sleep, stress, eating and drinking, and workout habits.

When clients reply to just a few texts each day, Verb’s AI converts their responses to data points that coaches use to provide a variety of personalized workout and stress management plans.

The application had been in testing for about year when the pandemic hit. Until then, Miceli had been the sole coach on the platform, working with a small group of about 100 clients to improve the product.

Seeing the effect the pandemic had on the fitness market, Miceli and Kiulian decided to launch their service in April for anyone to use.

“We knew that people were out of work, people were stuck at home. There’s a lot of odd challenges going on that we’ve all either navigated well or not over the past year,” Miceli said. “That was really our first stab at seeing how the public responded to the product.”

The response was better than Miceli could have expected. Within three months of launching, Verb saw nearly 16,000 new clients and 300-400 new coaches sign up.

As gyms continued to close and physical distancing guidelines were enacted, Verb’s user base grew, and the company found itself struggling to find enough coaches to serve its clients.

When searching for new coaches, Verb looks for a unique kind of person. In addition to basic coaching and training certifications, the company wants a specific set of soft skills. Coaching styles range from soft-spoken to drill sergeant-esque, and each has its place, but the common characteristic Miceli seeks out is empathy.

A good coach, he says, sets aside their own presuppositions to evaluate what the client wants. Coaches with the ability to have a two-way conversation and assist people in navigating their own paths through a problem are the most likely to help clients succeed.

Putting it all together

Miceli got his first glimpse at FitOps and the quality of the veteran trainers the program produced at a charity event in 2019 at Performix House, Hesse’s elite Manhattan gym. From then on, Miceli started running into FitOps coaches at gyms, retreats and fitness events wherever he went.

“It was just repeatedly popping up and put in our face,” said Miceli. “As we started to have conversations around it, it just started to really make sense.”

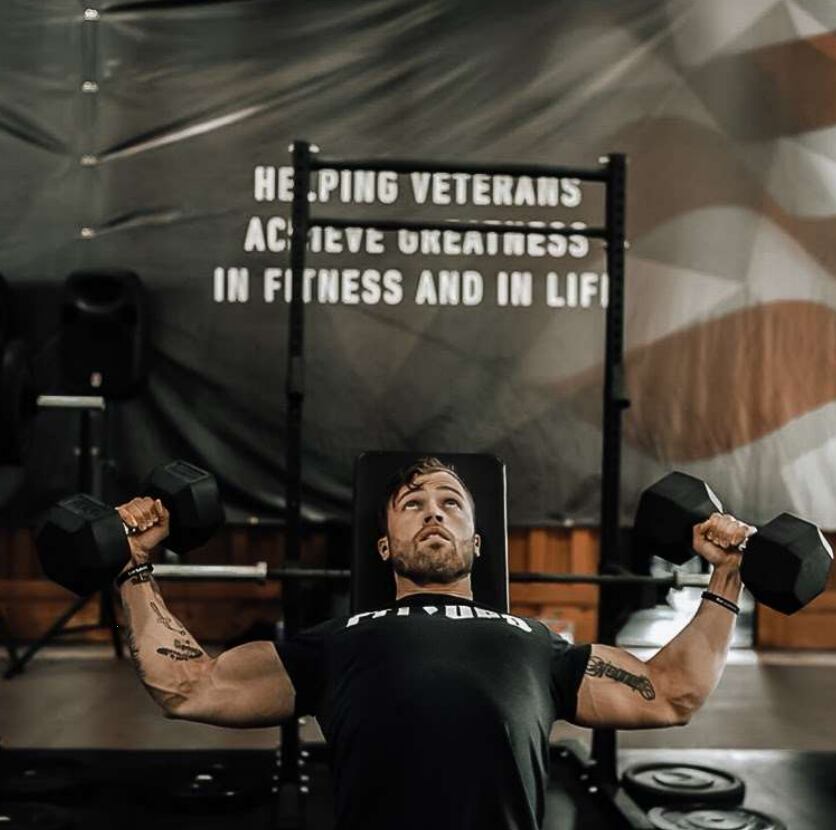

The way he sees it, veterans are already equipped with many of the skills needed to succeed in the fitness industry.

“Besides what they’ve gone through in their own military training… they have some life experiences that the normal person might not have encountered,” said Miceli. “So, I think that they have a deeper understanding of some of the trials and tribulations that can go along with identifying and achieving a goal.”

Completing FitOps training is the icing on the cake. When veterans add personal training certifications to their repertoire of interpersonal skills and life experiences, Miceli said, they become well-rounded coaches capable of walking alongside clients to reach goals.

The two organizations announced a partnership in early February that would meet both their needs. Verb’s shortage of coaches was filled with certified veteran fitness operatives — about 30 so far, and FitOps has been able to offer every graduate a chance at monetizing their skills in a time of gym shutdowns and stay-at-home orders.

“I’m really enjoying it. It’s a very digestible way to communicate with a large number of people, because everyone has a phone on them now,” former Marine Corps sergeant and FitOps graduate Mason McGuff said.

With the help of Verb, McGuff has been able to train clients from much further than six feet away.

On a typical work day, McGuff will begin training clients at 5 a.m. for the gym he works at in Oceanside, California. By 10 a.m. he’s moved to his phone and computer to spend the next four hours of his day coaching clients on Verb.

McGuff, who had worked as a personal trainer in college, graduated with FitOps Class 10 in the spring of 2020. While at camp, he was able to apply and interview for coaching positions with gyms across the country. By the time he graduated, he knew exactly where he was going.

But when the coronavirus hit California, McGuff’s gym was often shut down for weeks at a time by government orders.

As the partnership developed, FitOps’ aftercare program got McGuff connected with Verb, and he began coaching on the platform in January.

One month later, McGuff says about 20-25 percent of his business comes from training clients on Verb.

“That’s really no one’s fault but my own,” he said. “The platform really allows you the opportunity to kind of expand as far as you’d like, whether you want to be a part-time coach or a full-time coach.”

Virtual coaching comes with a steep learning curve, McGuff explained, but the virtual interface and data points provided by Verb’s AI make it easy to overcome any apprehensions clients may have.

“It does take a certain set of intrapersonal skills, but it gives you that quality time to get to know each and every one of your clients so that you’re establishing that rapport almost immediately,” said McGuff. “And it’s not as intrusive as it might be if I were a gym employee.”

Looking to the future

Clients aren’t the only population Verb is hoping to look out for. As the platform grows and develops, Miceli wants to see it used to connect veterans and facilitate opportunities for FitOps’ aftercare initiatives to help coaches thrive.

FitOps also has plans to grow. Though it’s had to close its doors temporarily to new students, the organization shifted its focus to growing its facilities during the pandemic.

According to Johnson, FitOps recently purchased a 500-acre plot of land in northwest Arkansas and is beginning to construct a national training center to serve as the site of future camps and training opportunities. The organization is also working to become a certified DoD SkillBridge internship.

Since 2016, FitOps has qualified nearly 400 veterans to be personal trainers. Classes are capped at a 36-person limit to ensure quality interaction between students and instructors, but the organization is capable of serving up to 2,500 students annually.

With its current structure and plans for growth, FitOps is the most comprehensive personal training certification program for veterans, but it isn’t the only way into the growing industry.

Personal trainers were projected to make up 12.1 percent of the fitness industry, or nearly $4 billion in revenue, in the last year alone, according to market researcher IBISWorld.

“There are more 750,000 personal trainers in America. Verb’s infrastructure can easily scale to the thousands, and our expectation for 2021 is to onboard 10,000 plus coaches on the platform,” said Miceli.

For current servicemembers and veterans interested in careers in personal training, McGuff recommends researching a market and building up people skills.

“Do your homework as far as what your market is and then find out exactly what that employer is looking for as far as your certifications,” McGuff said. “Be willing to negotiate, because you do have valuable training experience that you might not even be aware of.”

Miceli emphasized getting certifications as well, advising veterans who aren’t able to get involved with FitOps to still pursue some of the many different training opportunities available in nutrition, fitness and mental health. The Verb founder welcomes trainers of all backgrounds to apply to work on the platform.

“For what goes on with veterans after the service they give us as a country, to even be involved in or thought about in a way that we can partner with an organization like FitOps and do that with them has been amazing,” said Miceli. “The honor is on me, and it’s really exciting to be involved.”

Harm Venhuizen is an editorial intern at Military Times. He is studying political science and philosophy at Calvin University, where he's also in the Army ROTC program.