A U.S. Army Black Hawk crew may not have heard critical air traffic control messages instructing it to fly behind the commercial regional jet it ultimately collided with midair at Reagan National Airport in Washington on Jan. 29, the National Transportation Safety Board said Friday.

Additionally, the helicopter crew may have received inaccurate altitude data inside the cockpit, NTSB officials said at a media briefing at NTSB headquarters about the ongoing investigation.

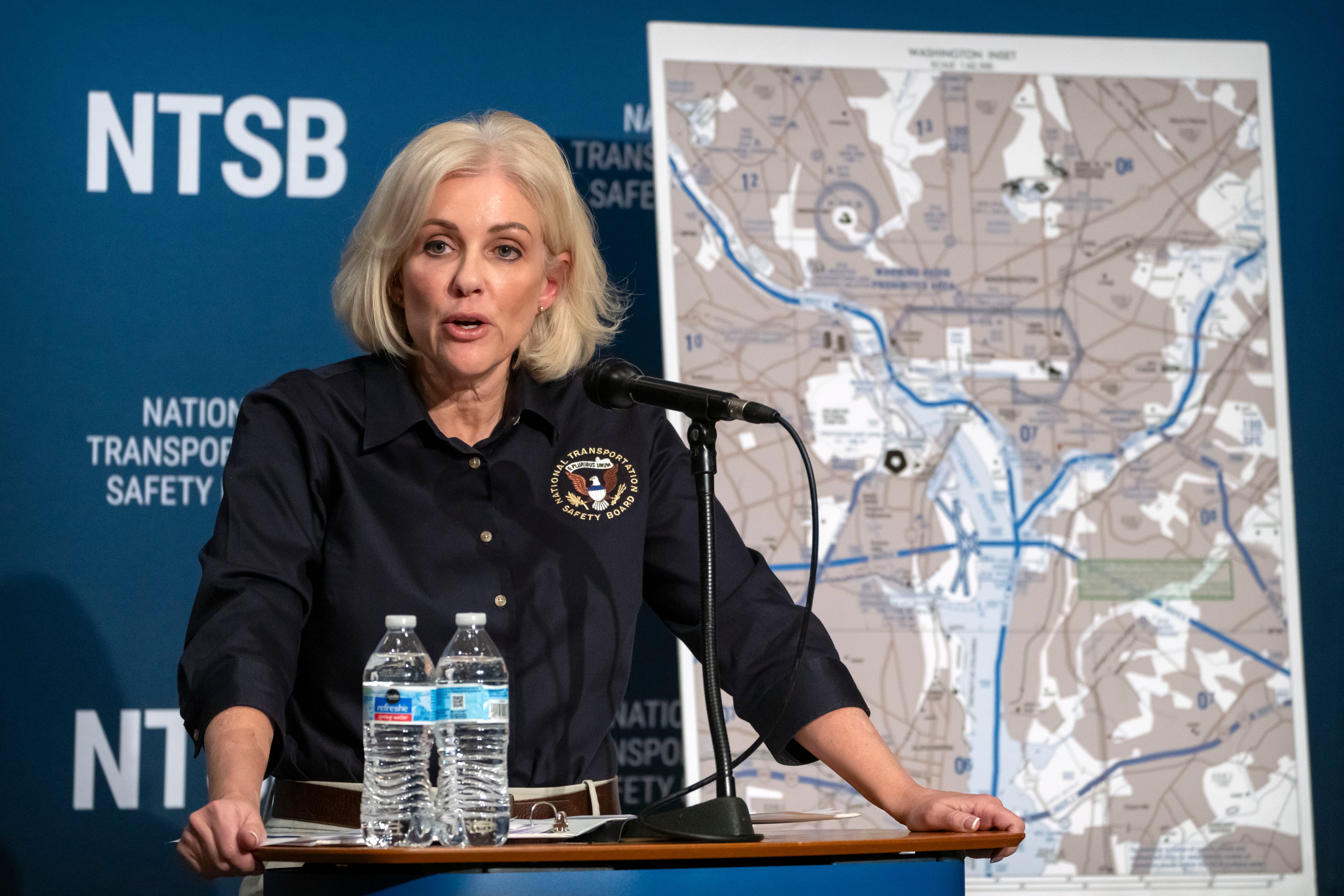

The on-scene investigation of the collision of the American Airlines flight from Wichita, Kansas, and a UH-60 on a flight over the Potomac River has concluded, Jennifer Homendy, NTSB chair, said. The investigation will continue off-site in various labs and other secure locations.

RELATED

When the aircraft collided, the fuselage of the commercial jet broke apart in three places and was discovered inverted in waist-deep water in the Potomac. The helicopter wreckage was found nearby. All 64 people aboard the passenger jet and all three Army crew members aboard the Black Hawk — Chief Warrant Officer 2 Andrew Loyd Eaves, Cpt. Rebecca M. Lobach and Staff Sgt. Ryan Austin O’Hara — were killed.

When asked if there was any indication the Black Hawk crew could see the impending collision in the seconds before impact, Homendy said NTSB investigators “do not have any indication” that the crew would have seen it.

Homendy also said it is now believed the helicopter crew were likely wearing night vision goggles throughout the flight because the check-out flight for the pilot was particularly focused on testing their ability to fly with the goggles.

“Had they been removed, the crew was required to have a discussion about going unaided,” Homendy said. “There is no evidence on the cockpit voice recorder, or CVR, of such a discussion.”

The NTSB will be conducting a visibility study to see what the crew would have been able to see or not see using night vision goggles leading up to the collision, according to Homendy.

Messages ‘may not have been received’

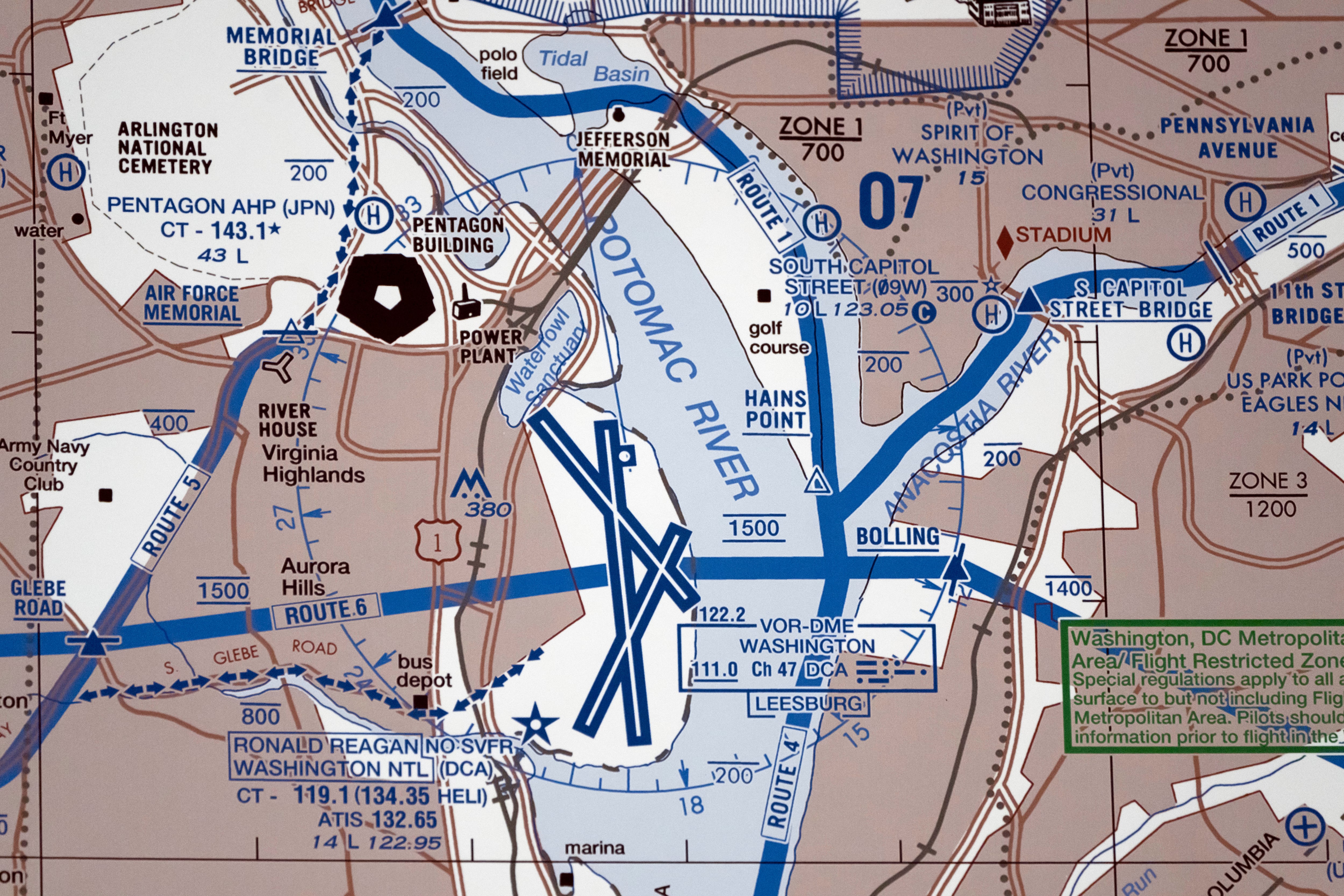

About two minutes before the collision, at approximately 8:46 p.m. local time, a radio transmission from the tower could be heard on the commercial jet’s CVR informing the Black Hawk that just south of the Wilson Bridge was a jet at 1,200 feet circling to its designated runway, according to Homendy.

Data from the Black Hawk’s CVR “indicated that the portion of the transmission stating the [jet] was circling may not have been received by the Black Hawk crew,” Homendy said.

“We hear the word ‘circling’ in ATC [air traffic control] communications, but we do not hear the word ‘circling’ on the CVR of the Black Hawk. The [NTSB] Recorders Group is evaluating this right now,” she added.

About seven seconds later, the Black Hawk crew responded to air traffic control that they “had the traffic in sight.”

Twenty seconds before the crash, “a radio transmission from the tower is audible on both CVRs asking the Black Hawk crew if the [jet] was in sight,” Homendy said. “Audible in the ATC radio transmission was a conflict alert in the background.”

The traffic alert and collision avoidance system on the jet received an automated traffic advisory “stating ‘traffic, traffic,’” she noted.

Three seconds later, a radio transmission from the tower could be heard in both CVRs directing the Black Hawk to pass behind the jet.

“CVR data from the Black Hawk indicated that the portion of the transmission that stated ‘pass behind the’ may not have been received by the Black Hawk crew,” Homendy said. “Transmission was stepped on by a 0.8 second mic key from the Black Hawk. The Black Hawk was keying the mic to communicate with ATC.”

The helicopter instructor pilot can be heard telling the pilot flying that “they believe ATC was asking for the helicopter to move left toward the east bank of the Potomac,” Homendy added.

‘Bad data’

Preliminary investigations are showing the pilot of the Black Hawk, flying 1.1 nautical miles west of the Key Bridge at approximately 8:43 p.m., indicated the altitude was 300 feet. The instructor pilot indicated the aircraft was at 400 feet.

The maximum ceiling altitude at Key Bridge is 300 feet above the terrain.

“At this time, we don’t know why there was a discrepancy between the two,” Homendy said. “That’s something that the investigative team is analyzing.”

At approximately 8:44 p.m., the instructor pilot indicated the Black Hawk was flying at 300 feet and descending to 200 feet as it approached the Key Bridge.

As the Black Hawk continued south passing over Memorial Bridge at approximately 8:45 p.m., the instructor pilot told the pilot flying that the aircraft was at 300 feet and needed to descend, according to Homendy. The maximum ceiling for flying south of Memorial Bridge is 200 feet.

“The pilot flying said they would descend to 200 feet.”

The radio altitude of the Black Hawk upon impact with the jet was 278 feet, which it had held for the previous five seconds, Homendy said.

“We’re confident with the radio altitude of the Black Hawk at the time of the collision, that was 278 feet, but I want to caution that does not mean that’s what the Black Hawk crew was seeing on the barometric altimeters in the cockpit,” she said. “We are seeing conflicting information in the data, which is why we aren’t releasing altitude for the Black Hawk’s entire route.”

According to Sean Payne, NTSB Vehicle Recorder Division branch chief, radio altitude is gathered by bouncing a signal from the helicopter to the ground.

“This is good data,” he said.

However, radio altitude isn’t the “primary means” the helicopter pilots would have used to determine their height during flight, Payne said.

“It is often different from what they see on their primary altimeters.”

Barometric altitude that pilots use while flying was not recorded on the flight data recorder, or FDR, also known as the black box. The barometric pressure setting was also not recorded.

Pressure altitude is also something that helicopter systems “can tap into,” Payne said. “We have found that this parameter is not valid,” Payne said, referring to it as “bad data.”

“We are working to determine if this bad data for pressure altitude only affected the FDR or if it was more pervasive through the helicopter’s other systems.”

The investigation will provide answers to what altitude the pilots saw in their gauges as they were flying, according to Payne.

The lab is working with Sikorsky, Black Hawk’s maker, and Collins Aviation, which handles avionic systems, and the Army to understand how the bad information could have affected other systems, he said.

Payne said the wreckage of the helicopter also needs to be examined, including the remains of pitot-static and air data systems, which he said will be difficult as the systems were “badly damaged” in the collision.

The lab will also look at the altimeters themselves to determine independent functionality, he noted.

“I’d like to stress that we’ve just completed the on-scene phase of the investigation,” he said. “We need to follow our process and be meticulous. Ultimately, this work will determine the altitude displayed to the pilots and will be included in our final report.”

Jen Judson is an award-winning journalist covering land warfare for Defense News. She has also worked for Politico and Inside Defense. She holds a Master of Science degree in journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Kenyon College.