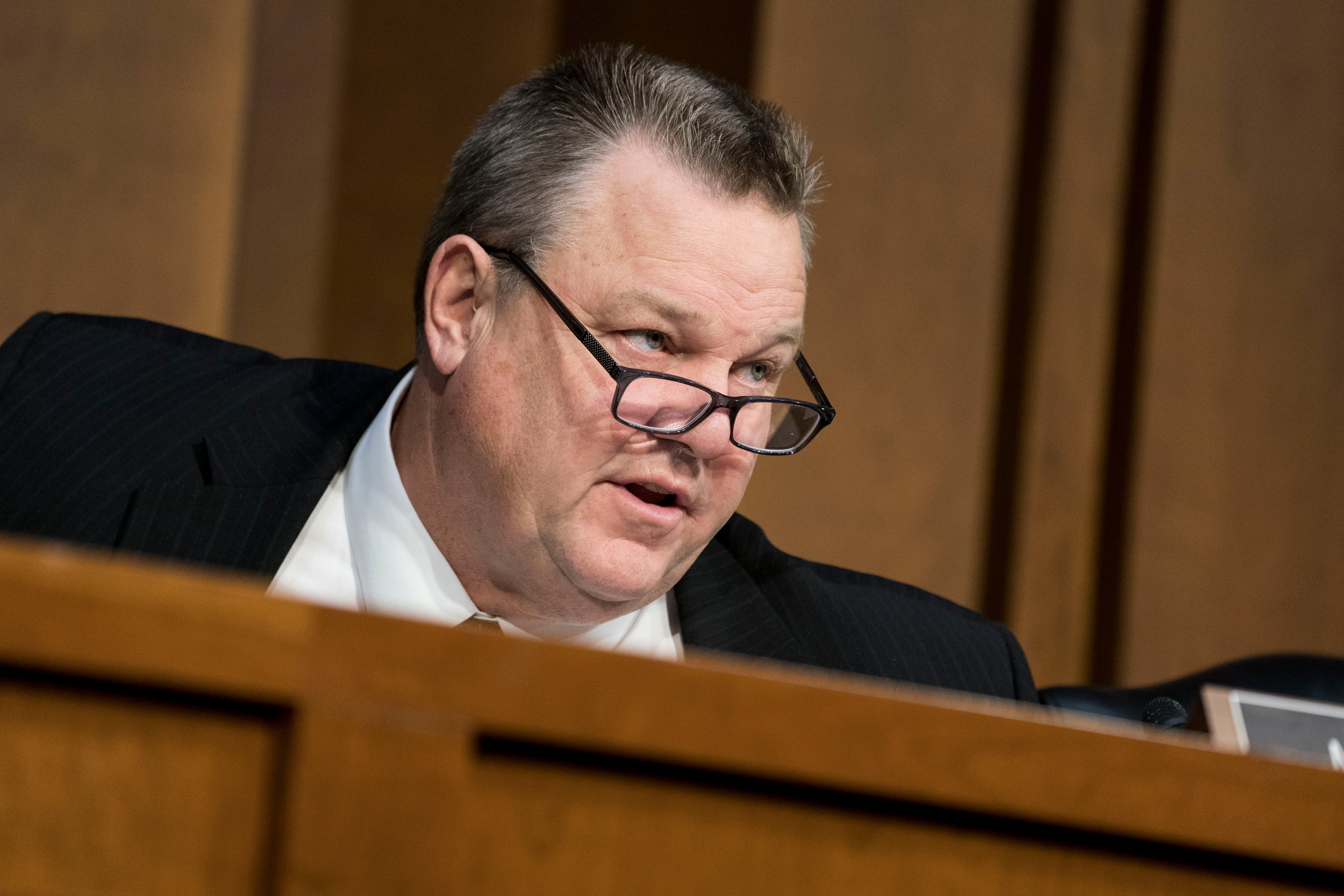

HIGH POINT, N.C. — Catherine Corpening’s hands tremble slightly as she clutches the small, well-worn book she’s just been handed.

Maybe it’s because she’s 76 years-old. More likely, it’s the sheer poignancy of this moment.

“Will you look at that?” she says, shaking her head in disbelief. “Where has this little book been all these years? I’d like to know the travels that it’s had.”

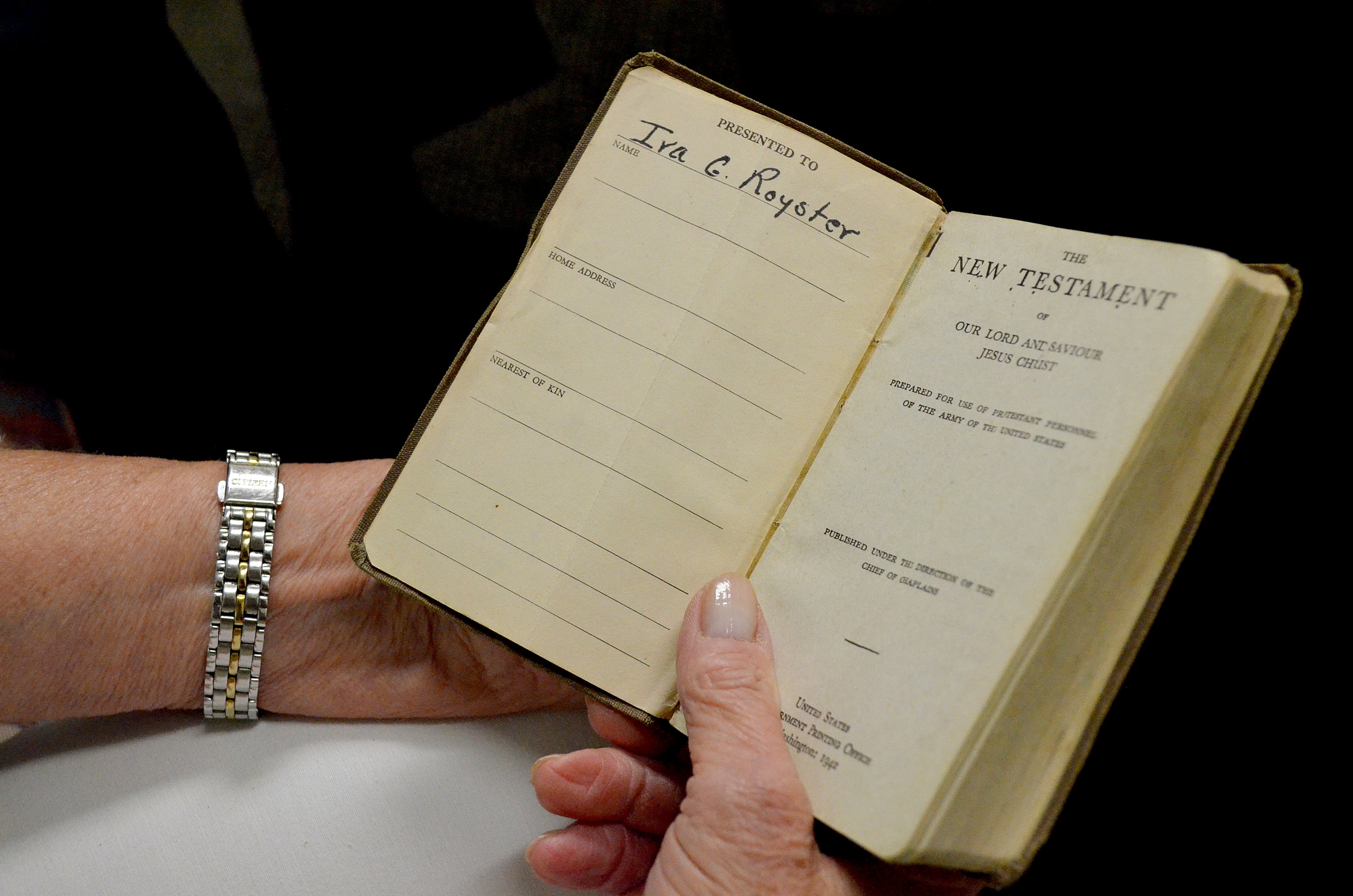

Her hands still shaking, Corpening eagerly, but gently, opens the cloth-bound hardcover book to a page near the front, where she finds the original owner’s name neatly handwritten in black ink: “Ira G. Royster.”

Her father.

Emotions rush at Corpening. Honestly, she never knew the man — she was only 4 years old when he died, shot down by enemy gunfire on a German battlefield during World War II. She has only one photo of her and her father together, and it’s a little bit fuzzy. In fact, because she was so young, she has only one memory of her father, and it’s fuzzy, too. She didn’t even begin learning much about his life — or his death — until after her mother died in 1999, when it was too late to ask her about him.

“She didn’t talk much about him, and I didn’t ask because I didn’t want to upset her,” Corpening explains. “My mama was a 23-year-old widow with a 4-year-old and a 6-month-old. That had to be hard on her.”

And yet now, as she stares at her father’s name — frozen in time, some 75 years after he wrote it — none of that matters. What matters now is that this book — one more piece to the puzzle that is her father’s short, heroic life — belongs to her now.

“That’s my daddy,” she says softly, absent-mindedly running her finger across his name.

Corpening, who was born and raised in Statesville but now lives in Hickory, doesn’t know where the little brown book has been the past seven-plus decades. Nor does she fully understand the chain of serendipity — “it’s such a miraculous thing,” she says — that eventually placed the book in her hands one afternoon last week in High Point.

She just knows that when Ira Royster enlisted in the Army in September 1942, he received this book, a pocket-sized New Testament with an introduction by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Royster wrote his name in the Bible and, as did many other soldiers, probably placed it in his shirt pocket, where it offered a shield of protection for his heart should a bullet or a piece of shrapnel come flying his way.

Now, three-quarters of a century later, the Bible belongs to Corpening — thanks to a High Point couple’s generosity and diligence — and she vows to carry the small heirloom where her father did.

Close to her heart.

Calling Don Little a World War II buff would be like calling World War II a skirmish.

“I mean, the man watches black-and-white World War II documentaries for fun,” says Little’s wife, Susan. “The films the rest of us were forced to watch in classrooms, he watches for fun.”

So three years ago, when the High Point woman was browsing at her favorite Goodwill thrift store in Winston-Salem and spotted a threadbare, pocket-sized New Testament that had belonged to a soldier during World War II, she envisioned it as a unique keepsake for her history buff of a husband. And when she noticed the Bible’s publication date — March 6, 1941 — matched Don’s birth date (March 6, 1958), she knew she’d found him the perfect birthday gift.

And what a bargain — she paid less than a dollar for it.

Susan soon realized, though, she couldn’t keep her surprise a secret for nine more months until March, so she decided to give the Bible to Don for Father’s Day instead. He couldn’t have been more thrilled.

“He was especially fascinated with the soldier’s name in the front, and he immediately zeroed in on that,” Susan says. “He had to know who this man was.”

A little online digging turned up all kinds of facts about the soldier, Ira Gay Royster: He was born in 1917 in Greensboro, but his family moved to Statesville when he was young. He married, had two small children and ran an insurance agency until September 1942, when he enlisted in the Army. After going through training, he served with the 311th Infantry Regiment, 78th Division, Company C, leaving for overseas duty in October 1944. He attained the rank of technical sergeant.

Don eagerly absorbed the young soldier’s story, but there was more.

On Feb. 3, 1945, Royster was seriously wounded, receiving several gunshot wounds as his unit was assaulting a heavily defended village in Germany, near the Belgian border. Sixteen days later, at an Army field hospital in Germany, he died of peritonitis and toxic hepatitis. He was buried in the beautiful, serene Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery in Belgium, alongside nearly 8,000 of his fallen brethren.

After reading about Royster’s death, Don — as much as he cherished the pocket Bible — no longer wanted it for himself. He had no idea how the Bible had ended up in that thrift store, but it didn’t matter now — he knew it wasn’t rightfully his.

“I need to find Royster’s family,” he remembers thinking. “This Bible belongs to them.”

His mission clear, Don posted messages on various veterans’ forums online, trying to locate a family member of Ira G. Royster, but to no avail. Surely, the soldier’s widow would be dead by now, and perhaps the two children, too, he surmised. Maybe he was just wasting his time.

At the suggestion of a friend, though, Don contacted a High Point Enterprise reporter for assistance, pretty much as a last resort. Within a matter of minutes, an Enterprise search turned up the name of a daughter, Catherine Royster Corpening, living in Hickory — less than 90 minutes from High Point. What were the odds of that?

By the end of the day, the two had connected over the telephone — what a conversation that must’ve been — and an overwhelmed Corpening was making plans to come to High Point to reclaim a precious piece of her family’s history.

---

It’s been that kind of year for Catherine “Cat” Royster Corpening.

She already had her father’s Purple Heart and other war medals — she inherited them from her mother — but earlier this year, she realized she didn’t have one medal she knew her father had earned, the Combat Infantryman Badge. Her congressman, Rep. Patrick McHenry, helped her navigate the red tape to have the medal sent to her, but when it finally arrived, there was a surprise in the package with the badge — a Bronze Star.

“He was awarded the Bronze Star posthumously, and we didn’t even know it,” says Corpening’s husband, Alex. “Cat’s mother never knew about it, either.”

So this year alone, some 72 years after her father’s death, Corpening has received two of his medals — one of them the coveted Bronze Star, for heroism in a combat zone — and now his Bible, which she didn’t even know existed.

“It’s all just so unbelievable,” she says. “I still can’t believe it.”

Corpening and her husband drove to High Point on July 21 to meet Don Little and get her father’s New Testament — a moment Don would call “an honor” and “a huge thrill.” She brought with her as many mementoes of her father’s military life as she could find, which in themselves tell the poignant story of Ira G. Royster’s life and death:

His medals, including the Purple Heart and the recently acquired Combat Infantryman Badge and Bronze Star.

A photo of the young, handsome soldier.

An insignia patch representing the 78th Infantry Lightning Division in which he served.

A miniature hand-carved rifle, which he sent to his young daughter from overseas.

The dozens of letters he wrote to his wife, Thelma, each one telling her not to worry, that he was going to be OK and looked forward to coming home.

The telegram he sent to Cat, which were essentially his last words to her. “My thoughts and prayers are with you,” he wrote. “Best love, from Daddy.”

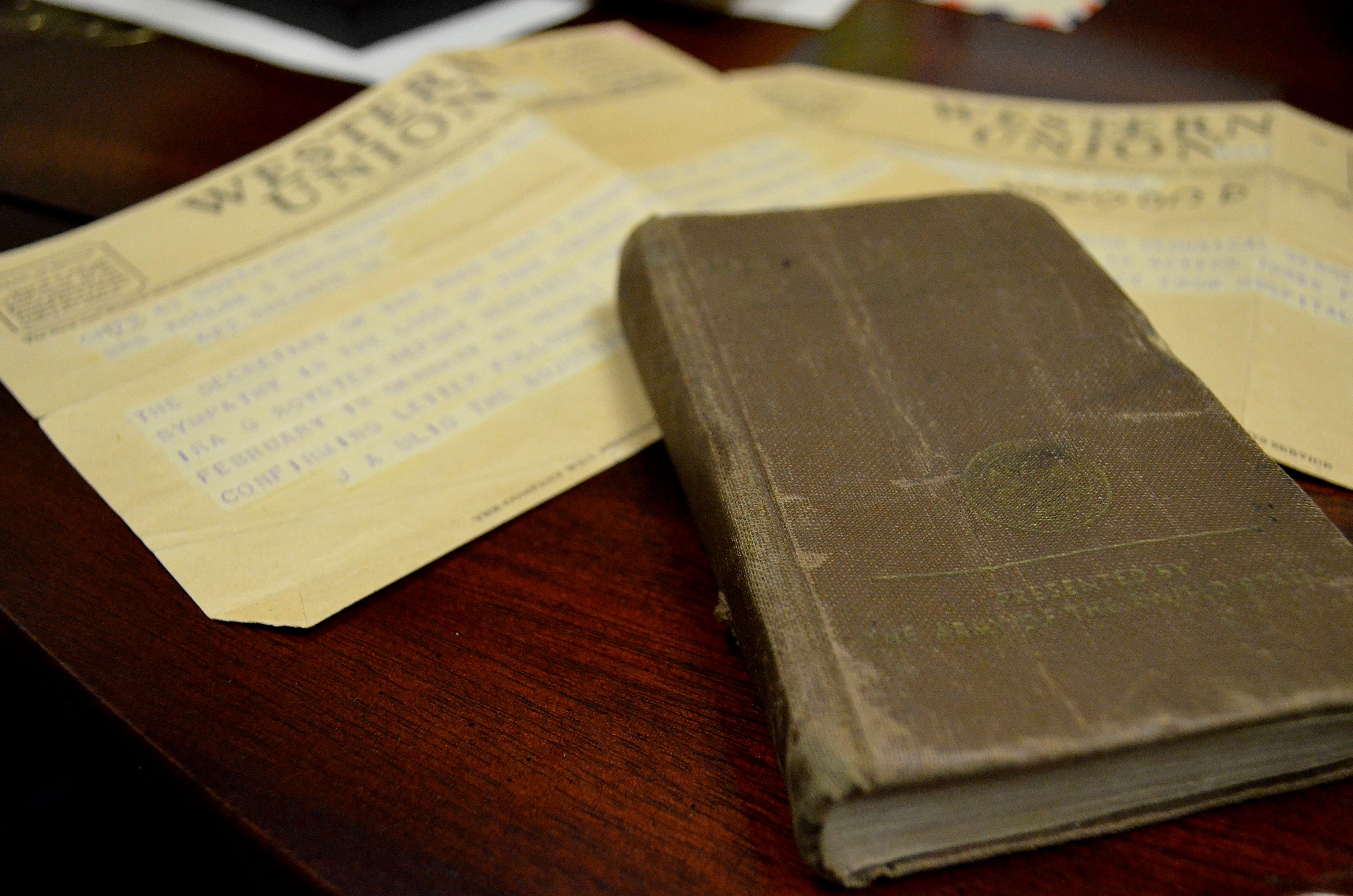

Two telegrams to Thelma, one alerting her that her husband had been wounded, the second informing her he had died.

A newspaper clipping about his death.

The American flag that draped his coffin.

A letter from one of her father’s Army buddies, and another from his first sergeant, both expressing their condolences and telling Thelma how brave and heroic her husband had been.

A framed photo of his gravesite at the cemetery in Belgium, which Cat has visited three times.

Her father’s bloodstained wallet, which he carried with him when he was shot. The wallet includes numerous family photos, including some of his young daughter.

For nearly an hour and a half, Cat and Don talk — mostly about Cat’s father, the virtual stranger who had brought them together. Cat tells how he had volunteered for the Army, even though he hadn’t been required to because he had two small children. She talks about her lone memory of her father, a vague image of them sitting in a cafe booth together somewhere and him eating a plate of fried eggs. She tells about the memory of seeing her mother sitting by a window crying after learning of her husband’s death.

Meanwhile, Don shares the story of how he came into possession of the small pocket Bible.

“You know,” he says, “when you find something like that in a Goodwill store, you think maybe it’s there because there’s no family left.”

This time, though, he and his wife are glad that wasn’t the case.

And, of course, Cat couldn’t be more thrilled. As she rises to leave, she gives Don a warm hug and thanks him again, still clutching the Bible in her hand. Eventually, she’ll put it in a shadowbox with the American flag and other mementoes.

“My daddy’s Bible is back home now,” she says. “Where it belongs.”